.

It’s a household appliance most of us would struggle to live without. But there are compelling arguments for doing less washing, less often. There’s the financial and environmental cost of electricity and water and the pollution from detergents, conditioners and synthetic fibres. Plus, washing wears out our clothes, so they need repairing or replacing sooner. Clearly, some things need washing after each wear. Regardless, there are small changes we can make to minimise the impact of our washing on our clothing, and the environment.

- Limit synthetics and invest in a Guppyfriend for any you have.

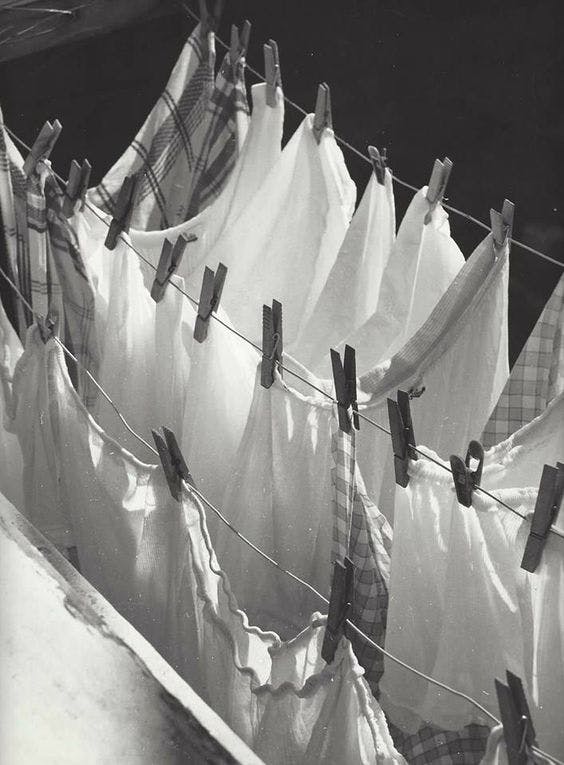

- Instead of washing after each wear, spot-clean lightly-worn garments and air outside to refresh.

- For actual dirt, even Stella McCartney suggests letting it dry, then brushing off with a clothes brush.*

- Treat stains before washing then use the coolest setting possible - and don't under- or over -fill the machine.

- Measure detergents carefully and find a formula that's free from (surprisingly common) harmful chemicals.

- Air dry clothes whenever possible: no fabric conditioner smells as good as line- dried laundry!

Credits: @stinaninnas, @anastasia.lisitsyna, Kess Scherer, Henk Jonker, William Abranowicz

Until they were replaced by synthetic dyes around 150 years ago, dyes were derived from an intriguing variety of flora and fauna; cochineal insects are still used to create red dyes, including the common food colouring, carmine. Now, awareness of the devastating effects of modern textile dyeing processes on people and the environment* has sparked a renewed interest in natural materials and techniques.

loaded with residual dyes and hazardous chemicals - into waterways, typically in regions of the Global South, where the majority of clothing production now takes place. But a growing body of makers are reviving traditional techniques, bringing the beauty of natural dyes to a new audience. One such is Ceilidh Chaplin, who documents her hand-dyeing projects on instagram and youtube, with visually-stunning results.

While some natural dyes create subtle tones, others can produce unexpectedly vivid shades, right across the colour spectrum. Some are simple, using everyday ingredients while others, like indigo, require several steps and more time and expertise. Most require the addition of a 'mordant' to intensify colours and prevent fading; mass production favours highly toxic heavy metals but sodium chloride (salt) and acetic acid (vinegar) are both traditional mordants. (A word of warning: brands might talk up their use of natural dyes, but the mordants might still be the toxic kind.)

Credits: @kornelia.lo @caramariepiazza

Sources: fashionrevolution.org/the-true-cost-of-colour-the-impact-of-textile-dyes-on-waters-systems

And not only synthetics, with their troublingly persistent micro-fibres.Even natural materials have remarkable longevity; if they’re properly cared for, they’ll stay looking good for years and even decades.So what happens to clothes after we’ve gone, or given them away? Where does their journey end?

Those with sentimental value - the wedding dresses, Christening gowns and jewellery box contents - may be passed on as treasured heirlooms. But what of the everyday things, the pieces we live in, day in, day out; shaped by our bodies, infused with our smell?

In some cases, nature can help. 100% natural means 100% biodegradable: in the right conditions, un-dyed linen can decompose in as little as 2 weeks; cotton in 2 months. (Wool and vegetable-tanned leather take a little longer). But chemical dyes complicate matters, hampering biodegradability and contaminating soil and water.

If we have looked after them, they might find their way into another person’s grateful hands.

And if not? Textile recycling sounds like the perfect solution, but the reality is more complicated.

Around 70% of all reused UK clothing is exported*, mostly to Ghana**. The Kantamanto market in Accra sees 15 million garments every week, in a country of 30 million people*** Of that, 40% goes unsold, destined for landfill or burning. Donating to charity is undoubtedly better than the bin, provided it’s in a condition you’d be happy to buy yourself. But before that, ask: can it be altered or upcycled, so I can still wear it? Can I give it or sell it to someone who definitely wants it? And before that, ask: how much do I need this, and what will happen to it afterwards?

Credits: @teklafabrics

Sources: Wrap, via www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-30227025

Statista.com, eco-age.com/resources/decolonsing-fashion-dead-white-mans-clothes-ghana/